What happened to ‘Man like Fatlum?’: The inside Story of the British Suicide Bomber of Ramadi

By Tam Hussein (All Street scene photos by author others public)

July 21, 2015

This is the back story of Abu Musa al-Britani, a young British suicide bomber who blew himself up in Iraq. He grew up in Ladbroke Grove, the area that I worked and grew up in as a youth worker. We also went to the same school. My essay seeks to answer the question as to why such a popular young man went to Iraq when he had planned a trip to Spain two weeks earlier. What compelled him to go, it also seeks to explain why the like of him and Jihadi John came from the same area. What are the factors that lead to their choices?

It is clear that neither foreign policy nor ideology are solely responsible for motivating European youth to go on Jihad. My essay argues that the reason many of these men went to Syria and join specifically ISIS is due to the subtle interplay between religion, foreign policy and gang culture and modernism. … [quoted from Tam’s email to me]

Tourists and bohemians love rummaging through the stalls on Portobello Road with its shimmering trinkets and shaggy clothes fit for an art student. To the locals it’s a “joke ting” , a skank to bring tourists from all over the world to sample the latest authentic “efnik” fad. Down the road on Golborne road, a stones throw away from David Cameron’s Notting Hill, young British Moroccans feast on platters of seafood on Hassan’s Grilled Fish stall laughing at the antics of their respective football teams.

Fatlum with Mohammed Nasser.

Some wear the latest garms others wear the trademark white thobe, full length beard, trousers above the ankle and Nike trainers like many Salafis do. Across the road Lisboa Patisserie is packed with locals and Moroccan old timers chomping on the best custard tarts in London talking about their worries, the way they might do back home. Here on the Golborne Road, West London, the Roadman rubs shoulders with the affluent city banker and never do their worlds meet, unless the Roadman is invited to a party to dispense a bit of coke. This is where Trellick towers estate sits easy with the bohemian Portobello Road. You wouldn’t expect a young native of these parts to cancel his ticket to a Spanish holiday resort, and instead end up a thousand miles from home and hearth, fighting in Iraq on behalf of ISIS.

Fatlum in school uniform, note the Westside gang sign he makes.

This is the story of Fatlum Shalaku, or Abu Musa al-Britani; the one who raised his index finger to the sky testifying to the oneness of God and rammed a truck laden with explosives into an Iraqi army position in Ramadi. The twenty year old Zayn Malik lookalike, handsome and muscular; popular with the ladies broke the Golden Division. The US trained special forces unit had been holding a defensive line for fourteen months and suffering heavy losses. His actions forced them to abandon the capital of Iraq’s Anbar province.

Word in Ladbroke Grove got out pretty soon. “Heard about Fatlum?” said one, “madd ting.” On the following Friday, we sat on the floor listening to the Imam at Ladbroke Grove’s Al-Manar mosque talking about how to prepare for Ramadan. I doubt the Imam had heard about the news, for if he had perhaps he would have addressed it. Fatlum’s friends didn’t quite know what to make of it and might have appreciated a talk on this issue coming from an Imam who was quoting the very scholar that ISIS revered; Ibn Taymiyyah, the 13th century Syrian scholar, the progenitor of the Salafi movement. But instead, he reminded his worshippers about the virtues of Ramadan; about the tendency to over eat during the holy month, the tendency to smoke shisha in cafes as people wait for the dawn prayer, the tendency to sleep well into the afternoon, and generally not benefit from the abstemiousness which should enrich the soul. But to some of the younger worshippers there was a need to make sense of his death. They talked about it with a sense of surprise and stupefaction. “I used to see him at the gym; lovely guy” said one, “can’t believe what he did.” In the estates around the mosque the young knew he had gone to fight in Syria but few expected him to go out like that. Another friend said, “Fatlum’s world view was twist but I know his heart was pure”. There was begrudging admiration for the young man who walked the walk even though he hadn’t talked much about it. A former school mate put it differently to ITV news: “it is sad, we have to ask ourselves why a person full of dreams and possibility and potential …would…blow them selves up.”[1] Everyone seemed to say what happened to man like Fatlum?

Golborne road North African shop

Outside of Ladbroke Grove, little is known about Abu Musa al-Britani. He didn’t have a large social media footprint. Fatlum had deleted his Facebook account before leaving for Syria according to his friends. He came from a Kosovo Albanian family and attended Holland Park School. Fatlum enjoyed his time there and was described as “popular” and “friendly.” The school population reflected the diversity of the area and had a large British Moroccan and Somali community from Shepherds Bush, Latimer and Ladbroke Grove since the Nineties. Many like Fatlum, who grew up in North Kensington, were brought into the British Moroccan cultural orbit, after all nearly sixty percent of the UK’s British Moroccan population settled in North Kensington in the 70s and 80s.

Reminders of the home country

Some say that Fatlum was intensely moved by the Syrian conflict, but that is simply not true. When the Syrian revolution broke out as one friend of Fatlum said, “every one was gassed” about Syria. These young men were profoundly affected by the images coming out on social media. After all this is the most mediated conflict that the world has ever seen and anyone with beating heart would find it hard to bear witness to the despicable acts carried out by the Syrian regime. As a cousin said of Mohammed Nasser, a fighter and friend of Fatlum who was killed in Iraq:

“…[Nasser] was angry about what was happening in Syria…like Iraq and Palestine. I don’t think he was radicalised, he understood what radicalisation was and what extremism was…”

Fatlum knew of a mysterious convert, not unlike Ras in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, who packed up his bags and joined ISIS. This Ladbroke Grove Ras, rootless, charismatic and confrontational had gathered around him a group of young men in Ladbroke Grove who would eventually follow him. These young men recruited others through whatsapp and other messaging services. It was chain migration in reverse. Rumours has it that he was killed by Jaish al-Fath, a rebel faction that has made recent gains in Idlib. Speaking to a local, Elias, not his real name, the fact that there was a recruiter, was something the British security services must have been aware of in the Ladbroke Grove area. They were showing locals pictures of persons of interest.

Trellick towers next to Al-Manar mosque

But Fatlum wasn’t that hyped about fighting in Syria or swayed by this ‘recruiter’. Like his family, Fatlum was not religious and lived a relatively secular lifestyle like many Kosovo Albanians whose parents had experienced Communist rule. He was close to Mohammed Nasser and also knew Hamza Parvez, all ended up fighting for ISIS. One theory has it that Nasser influenced him to go to Syria. Nasser had found Islam after his father died; he has been described as a charismatic and passionate young man who influenced those around him. In contrast, Hamza Parvez was described by a family member as being “lazy” and a bit of a drifter, more interested in Krispy Kremes than fighting. He followed Nasser to Syria. Usually when a close circle forms around one or two charismatic individuals who are motivated to go, others are more likely to follow, irrespective of income or socio economic background. Those who are less wedded to aspiration and the good life, might have little to lose and a lot more to gain by going. Especially as the promise for them is either paradise or ghanima, war booty. Hamza Parvez may have fitted that type, but Fatlum didn’t. Speaking to his friends it is difficult to ascertain how much of an influence Nasser was on him. In fact, Fatlum left for Syria before Nasser. According to a cousin, Nasser “was a good guy and he knew right from wrong and he had compassion. He went to uni, played football…he wasn’t the sort of guy who argued about the caliphate. I never ever suspected he would go.”

A friend told me: “If any one influenced him it must have been his older brother, Flamur. They were close and Fatlum looked up to him. He rediscovered his faith a year into his degree at uni.” Flamur was a talented young architect whose work had been showcased by the Saatchi and Saatchi gallery. His transformation, according to another school friend, was overnight, going from someone who could “be seen socialising and drinking with friends” to someone who was assiduous in worship. He was often seen at Ladbroke Grove mosque attending the congregational prayer there. It was Flamur who drew his younger brother into discussions that led the latter to confront his own perceptions about life. But whilst Fatlum might have considered the big questions, two weeks before his departure to Syria, he was still interested in the usual stuff that the Ladbroke Grove mandem were interested in. Had it not been for his older brother talking him out of his Spanish holiday, Fatlum would have larged it with the ladies.

And yet, Fatlum’s decision to fight in Syria was not just a whim, but perhaps the flotsam and jetsam of various currents that coursed through the Ladbroke Grove area.

Religious Currents in Ladbroke Grove: The influence of the Salafi-Jihadis

Inside Manar Mosque

One of these currents was the religious element in Ladbroke Grove. As Raffaello Pantucci noted in ‘We Love Death as You Love Life,’ London had seen a religious revival long before Syria and long before 9/11. Ladbroke Grove in this regard was no exception. The Muslim community’s gradual confidence and religiosity found expression in the opening of Al-Manar Islamic Centre on Acklam Road in 2001. The airy mosque complete with school and sports facilities, with a hint of North Africa, was jammed in between Westway recreational grounds and a council estate. It was also an expression of the Moroccan community’s self-confidence. Now, a few decades on, and it sees about twelve hundred worshippers every Friday from all walks of life and counted amongst its congregation ISIS fighters likes Abdel-Majed Abdel Bary, Hamza Parvez, Mohammed Nasser, Flamur Shalaku, Choukri Elkhlifi, Mohammed El-Araj, and Aine Davies, who all prayed there from time to time.

Old Timer praying in Manar Mosque

The area was not unique in that diverse Islamic strands and traditions coursed through it. There was the traditional Islam brought over from Larache, Morocco. It was a mix of Maliki jurisprudence, scholarship and Sufi traditions. These traditions are found amongst the old timers who sit reading the Quran after the evening prayer at the mosque. Sit down with them and you will sense the rich scholarly tradition of Fez and Marrakech. The way the old timers taught Tajweed, the art of Quranic recitation to the youngsters is reminiscent of the master student relationship still alive in their home land. They come from a rich tradition of learning that had been distilled over centuries with a great deal of nuance. The student has to master Arabic, philology, grammar, Quranic exegesis, jurisprudence and moral ethics amongst other things and only then, would the teacher grant him an Ijaza or permission to teach. That sort of profound study takes more than a few years of an Islamic studies BA in any modern Islamic university. Few in Ladbroke Grove, least of all Fatlum, had time to go down that route.

Alongside this, you also had the competing modernist Salafi tradition inspired by Muhammed ibn Abdul Wahab, a revivalist scholar of eighteenth century. His movement called for strict monotheism and rejected the adherence to a school of jurisprudence, mysticism and precepts that appeared to be cultural additions. This view, believed that over-reliance on blind imitation or Taqleed of scholars was misguidance, and sought to connect the layman directly to the sources of religion and thereby get him closer to God. Salafism’s appeal was its simple call to authenticity. As one worshipper put it: “Islam is simple, all you need is Quran and Sunnah”.

But occasionally its adherents fell into a trap of interpreting the texts with out having the prerequisite skill-set. Salafism disliked ‘blind imitation’ as it was disparagingly known, or taqleed of a scholar. To the born again devotee on the Golborne Road in search of religious enlightenment, he didn’t need a religious specialist, he could just open up the Quran and take the canonical sayings of the Prophet as his guide; no middle man was required to distil that seemingly contradictory mass of Prophetic sayings and Quranic verses. To Salafism’s detractors though, this was exactly the problem. These novices were akin to a thirsty rabble drinking straight from the vast salty ocean instead of allowing the scholar to making the seawater potable. Drinking straight from the ocean would result in madness or at the very least hubris. This was something a family member complained about when Hamza Parvez found his faith:

“This was last year. He used to wear the thobe and he’d pray and what annoyed me most was when he started telling his mum what to do. It kind of gave him this superiority because he thought that she didn’t have any knowledge.”

And certainly the answers and scribblings on the tumbler pages, and Ask FM answers of some these ISIS fighters appear as if they were fatwas, or religious legal rulings.

Another offshoot of the Salafis in Ladbroke Grove was the Salafi-jihadi movement. As Jonathan Birt notes in Radical Nineties Revisited: Jihadi Discourses in Britain[2], the fact that many of these radicals and Salafi-jihadi ideologues were allowed to operate in the 90s so freely meant that the conditions were in place for it to flourish by the time Fatlum encountered it. As one young Imam who grew up in the area, told me West London has always had a strong Salafi-jihadi tradition. So disturbed was the young Imam that he decided move away from the area. The Salafi-jihadi movement in a nutshell, believes that only through Jihad can the Muslim global community restore its dignity and power; in some respects it is Fanonesque in conception. It is as Abdallah Azzam, one of its icons and the father of the Afghan Jihad put it, “Men need jihad more than the jihad needs men.” Salafi-jihadi thought was a response to the centuries-long decline of Muslim power on the world stage and the incursions of the West into Muslim societies.The communities in Ladbroke Grove through a mixture of faith and heritage were profoundly connected to the affairs of the Middle East, especially the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The US invasion of Iraq in 2003 resulted in Salafi-jihadi thought having a greater resonance in the community especially amongst the young. Fatlum’s older brother was certainly an adherent to the ideology and though Fatlum may not have been, in the company of his brother and like minded individuals he certainly became one.

Gang Culture and Religion’s subtle interplay

Skateboarding on the West way in Ladbroke Grove

But Fatlum also grew up in a milieu where there was a subtle interplay of religion and gang culture. In amongst the affluence of North Kensington, gang subcultures flourish. On the estates youth workers fight a constant uphill battle, not against radicalisation but the normal problems that most inner city communities face. The predominantly Moroccan community in the area face huge challenges in North Kensington. Myriam Cherti notes in Paradoxes of Social Capital: A Multi-Generational Study of Moroccans in London, in 1998, Golborne Ward fell under the 1 percent of the most deprived wards nationally[3], this situation changed little by 2012, when it was was ranked as the second most deprived in London[4]. The same author noted in a study for the Runnymede Trust, British Moroccans: Citizenship in Action, that poverty and disadvantage was “endemic in the area”. The youth workers I met were constantly trying to get young people to channel their energies into more positive activities. One of the bolder youth workers, Khaled, not his real name, told me, “I fork out money out of my own pocket; buy them chicken and chips and then they come to the sessions.” but with funding cuts these youth workers were struggling. Khaled complained that other youth clubs were receiving funding from different funding streams but those available to Moroccan communities were mainly through Prevent funding, the governments controversial anti-terrorism policy. This cynicism is not something recent. As early as 2009 the Runnymede Trust study states that: “smaller organisations complained that the Council discriminated in their funding practices, favouring certain projects whilst blocking others’ opportunities to develop.” Khaled explained that the bigger problem in the area is still drugs, knife crime, gang fights, teenage pregnancies and civil engagement rather than terrorism and radicalisation. To this youth worker, it didn’t matter that five young men had left the area to join ISIS, he had to scour the streets to stop “Kids stabbing each other over a mobile phone. Every young person is touched by gang culture around here”.

With marginalisation comes social problems. Drugs and criminality had always been a facet of Ladbroke Grove since the 90s. Golborne Road was the best place to pick up skunk and hash in West London. Anyone who grew up in the area knew that Ladbroke Grove had cornered the market. You could drive up in a car and some dealer would shake your hands drop the punk and walk off in his joggers. Any undercover would have a hard time finding this ghost disappear into the estates. But as time passed these men, coming mostly from the close knit Moroccan community, felt the impact of religion in their lives. Their parents were getting old and becoming increasingly devout. They started their own families in the area and with the profundity of having one’s own family they too began to consider the deeper meanings of life. “Once a man holds his own kids in his arms” said one, “he starts thinking about their future, you can’t help it. That’s just God’s way”. A few decades on and these same dealers who had shot the stuff to willing punters, were sporting beards and praying five times a day looking for ways to atone themselves. These men raised in the school of hard knocks found that Salafi-jihadism fitted their temperament just like perhaps a creative temperament might prefer a Sufi understanding of Islam.

With marginalisation comes social problems. Drugs and criminality had always been a facet of Ladbroke Grove since the 90s. Golborne Road was the best place to pick up skunk and hash in West London. Anyone who grew up in the area knew that Ladbroke Grove had cornered the market. You could drive up in a car and some dealer would shake your hands drop the punk and walk off in his joggers. Any undercover would have a hard time finding this ghost disappear into the estates. But as time passed these men, coming mostly from the close knit Moroccan community, felt the impact of religion in their lives. Their parents were getting old and becoming increasingly devout. They started their own families in the area and with the profundity of having one’s own family they too began to consider the deeper meanings of life. “Once a man holds his own kids in his arms” said one, “he starts thinking about their future, you can’t help it. That’s just God’s way”. A few decades on and these same dealers who had shot the stuff to willing punters, were sporting beards and praying five times a day looking for ways to atone themselves. These men raised in the school of hard knocks found that Salafi-jihadism fitted their temperament just like perhaps a creative temperament might prefer a Sufi understanding of Islam.

Despite the prejudice faced by the Moroccan community in North Kensington political engagement has always been high especially at local level. However, as the Runnymede Trust study found, there was also political discontent especially in the second generation. The invasion of Iraq in 2003 being the main boon of contention. The punishing decade of sanctions that preceded it with over half a million children dead and Madeleine Albright, US Secretary of State, quipping that the price “was worth it” jarred. To many in Ladbroke Grove, the Iraq war wasn’t a L’Oreal advert. Long before the area produced AQ adherents like Bilal Berjawi and Ramzi Mohammed, there were rumours that some old skool British Moroccans were expressing their political disenchantment by adopting Salafi-jihadi ideology and even trying to join the insurgency in Iraq. There was always talk of ex-Ladbroke Grove criminals suspected of a string of crimes in and around West London to fund their Jihadi activities. These criminal acts, it was said, were justified by the legal fiction that they were living in Dar al-Harb or ‘House of War’; a classical Islamic term developed by a body Islamic Jurisprudents during the medieval period to denote the lands that the Muslim world was at war with. Jihad as any jurisprudent will tell you was an all encompassing term referring to warfare that was nuanced, localised and differed according to time and place. So for instance, if the enemy mutilated your dead, you were not allowed to mutilate their dead because it was considered unjust and in direct contravention of God’s injunctions. Some of those rulings, albeit a minority, allowed for repaying the invaders of Muslim lands with the same treatment in extreme circumstances. That understanding allowed that everything was permissible, fraud, robbery, even enslaving women and so on. One worshipper told me, on condition of anonymity, that one “Grove man” had the audacity to rob a security van, and then turned up to offer Asr prayer at the mosque with the money box next to him, and after finishing casually walked off home with it. It was also rumoured that some of these men joined the smaller battalions within Syria’s splintered rebel factions like Katibat al-Khattab and Sham al-Islami brigades; the latter drew predominantly from North African participants.

Golborne Road

But one thing these Ladbroke Grove Salafi-Jihadis were not; unlike many of the younger generation of Jihadis; they were not blatantly Takfiri in outlook in the way ISIS adherents were. Although there were some exceptions, most refrained from making Takfir or excommunication. Compare for instance the latest comments made by the late AQ spokesman Adam Gadahn, regarding the execution of Alan Henning and ISIS’ position. The latter considered it a sin. Like it or not, Salafi-Jihadism does have a theological discourse, with its thinkers, scholars and traditions. Usually the older fighters from Gadahn’s generation kept to within that framework. They looked at the West as an oppressive colonising infidel power that needed to be opposed, those Muslims who took a different view, were not declared automatically infidels en masse. This type of Salafi Jihadi still had respect for tradition and the sanctity of Muslim blood, even if they had none for UK law. But nevertheless as one Imam who knows Ladbroke Grove and those that adopted that opinion, told me, “is it victory at all cost that these men wanted? By adopting such an extreme opinion, they essentially did away with any ethical considerations of the Sharia, did the Companions and the Prophet do any of these things they did? No of course not, what they did do was open up the flood gates for the next generation where they could do anything they wanted.”

Despite the obvious problematics of Salafi-jihadism within Islamic intellectual discourse as well as outside of it, the newly emerging strain of Salafi-jihadis was hard to grasp by the older generation. The old skool jihadists were now criticising Fatlum’s generation for spiralling out of control. In fact, most recently the Jordanian Salafi jihadi cleric Abu Qatada, one of its main ideologues, criticised young Westerners coming to Syria with no religious training killing Islamic Jurisprudents with years of religious learning. The new generation they said lacked tarbiyyah or sound upbringing; their sincerity was not enough. There was clearly a generational disconnect. In many ways the conflict between Nusra Front and ISIS is also a reflection of this conflict between Old Skool Jihadis versus the New Skool. This new strain of Salafi-jihadism was seen as even more radical, virulently takfiri; they cared nought for any tradition that would ground them, nor for scholarship, and any kind of normative except their own. This idea seems to be confirmed by Thomas Pierret, Lecturer at Edinburgh University and author of Religion and State in Syria: the Sunni Ulama from Coup to Revolution, in a post on Facebook he says of the older generation Jihadis they were:

“motivated by the will to defend fellow Muslims against oppression. Their propaganda was a never-ending complaint about the plight of Muslims across the world. ISIS-generation of foreign fighters are completely different. Their Propaganda and behaviour suggests that not only are they totally indifferent to the plight of the Syrians, but they’re happily imposing upon them a ruthless form of oppression as part of their narcissistic settler-colonialist utopia[5]”

It is true that young Ladbroke Grove Jihadis like Fatlum were different. According to a friend, Fatlum was “extremely Takfiri” in outlook, but he didn’t proselytise it the way other ISIS fighters did on social media. But to him the sacred and the profane was photoshopped with pop culture. These young men, in typical post-modern style comfortably mixed iconic images of Jihadica with Call of Duty. Sitting in an Italian cafe, Ali, a student who grew up in and around Ladbroke Grove told me even more bluntly what he thought the problem was; “There’s more to it, you have a high percentage of Roadmans who don’t know anything about the faith and they discover Anwar Awlaki on Youtube and it’s a disaster. On top of that everything they watch from Lord of the Rings to 300, to Saving Private Ryan to Black Hawk Down everything about the Western culture celebrates heroism and self sacrifice. Some of their fathers also fought in Afghanistan, they have a fighting mentality because of the streets and once you put religion into it; which says helping the weak and oppressed is good, you got a Jihadi Roadman. It’s so predictable. Notice that most of these Roadmans joined ISIS; the rest with any sense of the faith didn’t.”

Fatlum’s friend Mohammed Nasser was a case in point; going through his twitter feed you notice that Grand Theft Auto Five is mentioned in the same breath as martyrdom, even though GTA is probably the most antithetical to the Islamic moral ethic. On his twitter feed. He flitted from talking about his friends to messaging Pro-ISIS disseminators like Shamiwitness[6]. The connections they were making, the culture they were creating was one particular to their generation. They had their own terminology, they wore their Salafi-Jihadism on their robes, blended it with rebellious Roadmannism, garnished it with a bit of Anwar Awlaki, Quran,Sunnah and a bit of thug life. They could yearn desperately for forgiveness and paradise, and in their youthful ardour want a sense of belonging and adventure. West-side hyperbole turned into “the land of the Muslims have to be defended.” The new generation Jihadi Roadmans short circuited the Salafi-jihadi tradition for just Team Muslim-no matter what; the response was not un-similar to the American patriot who cried Team America: no matter what. These men no doubt sincere in intention had become a law unto themselves and could wreak havoc and go against well established Islamic principles. These men joined ISIS.

Flamur’s artwork brother of Fatlum

When Abdel Majed Abdel Bary, 23, from Maida Vale, held out a decapitated head and declared to his tweeps that he was: [8]‘Chillin’ with my homie or what’s left of him.’ To many it contradicted traditional concepts of chivalry and everything that Jihad represented. “No one is saying that war is a walk in the park, its ugly and nasty, but the whole point about Jihad is that when man has license to be at his most brutal, most callous, he doesn’t give in to his baser nature. It is easy to be clement, merciful and civilised in our everyday lives, but in war a man can actually show his true nobility, by being merciful, clement, and chivalrous, even when he has been wronged and his instinct is telling him to be brutal and unforgiving. And this is something that many fighters in ISIS have forgotten” said one Imam who asked to be anonymous.

A cursory glance through Medieval literature on famous Muslim warriors shows them to be cultured both in war and also the humanities, the autobiography of Usama bin Munqidh a 12th century knight during the crusades and Ibn Shaddad’s biography on Saladin for instance is testimony to that. Both are able to show magnanimity towards their enemies. Read Tolstoy’s Hadji Murat, a novella declared by the literary critic Harold Bloom to be “sublime” and you notice Tolstoy’s deep admiration for a Muslim warrior. A Jihadi who refused to give in to the demands of the world, least of all Tsarist Russia. Fast forward to the twentieth century to Abdullah Anas, a veteran of the Afghan Jihad and the son in law of Abdullah Azzam, and find a man disgusted by the antics of these young fighters who kill men and upload it on twitter. As he told me in his office in North London:

“Prisoners have full rights. We fed them the same food, gave them the same clothes and the same quality of life. After several months, many of the Soviet troops started to believe that they weren’t prisoners because we were on such good terms with them. Through our conduct we showed them we were not bloodthirsty people. Some of them became Muslims, others remain our friends to this day[9].”

To the veterans the Abdul Barys of this world were just expressing Roadmannism found in every day Ladbroke Grove, only the location was different. So what had happened in-between the period between Old Skool Jihadists and the modern day Jihadist who joins ISIS? According to Bilal Abdul Kareem, an American Muslim convert and freelance journalist who spent a considerable time in war torn Syria it seems to be a case of a ignorance and loosing one’s moral compass. Sitting in a cafe sipping a latte and relishing a chocolate chip cookie, he told me that some of these fighters “are extremely sincere in their intentions but because they don’t know the basics they attach themselves to a group who they think will take them to God, so they get played…I couldn’t believe it…we were inside a car once and they were discussing whether it was permissible to target women and children, I’m like brother, why are we even having this conversation?! Islam doesn’t allow that. That’s how ignorant they were.” Fatlum’s knowledge of Islam was at the time of leaving, described by friends as basic but continued under Islamic State proselytisers.

When Fatlum left it wasn’t just faith and the International community’s inactivity that pulled him there. There were complex factors at play, the influence of individuals, the interplay of Salafi-jihadi thought, Roadman culture, identity, or simply a need for adventure and atonement that made him get on that plane to Turkey. In spring 2013 the brothers went to Turkey transiting off a European country.

To their father, Muhamet, the news came as a complete shock. The brothers had kept their faith secret from the family. Once they were in Syria contact with family was intermittent. They told the parents that they were doing aid work. Fatlum’s mother fell into deep depression. Although the parents did not report the two missing immediately, their disappearance did not go unnoticed, the police were aware that they had left. The father said that special branch had visited them and taken their computers away. He perhaps naively, believed they would help to retrieve them. The officers were particularly interested in the two following the revelation of the identity of Jihadi John.

In Syria, what had started as a true revolution began to resemble 12th century Andalusia during the age of the Muluk at-Tawa’if or the Party Kings. Each emir of Andalusia’s fractured principalities, supported by various Christian kings, made war on each other for hegemony of the Spanish Peninsula. Many foreign fighters who had come to fight Assad, instead found themselves embroiled in this intra-rebel infighting. Abu Layth al-Khorosani, or Anil Khalil Raoufi from Manchester, for instance died fighting the Free Syrian Army instead of Assad. When the fighting broke out between ISIS and Nusra Front, to the surprise of one friend, the two brothers did not get involved in the internecine Jihadist infighting that broke out in January 2014. Fatlum made his choice quite early on. Contrary to reports, the two brothers did not defect from the Nusra Front but rather after they had finished their training with Katibat al-Muhajireen (KaM) led by Georgian national Omar Shishani and his former deputy Abu Mus’ab al-Jazairi, they joined ISIS. It is not clear why the two brothers left Katibat al-Muhajireen for Islamic State. Perhaps they followed Omar Shishani as he made his oath of allegiance or hoped to join a group that would take them to Paradise, it is hard to tell. Nevertheless their aloofness from fighting their former comrades earned them the respect even of their enemies. This may have been one of the reasons they ended up in Iraq, precisely because they wanted to avoid fighting their ex-comrades. Instead they preferred to fight the Shi’ites and the Kurdish YPG, the former who Salafi Jihadis consider to be heretics, and the latter who they view as godless Atheists due to their secular or communist beliefs.

Abdullah Anas in middle

Flamur Shalaku or Abu Sa’ad as he was known, was killed in March of this year in Iraq. His father, Muhamet received a phone call where a distant crackly arabic voice spoke in broken English and said: “Everything is good with your son”. The father was not devout, he didn’t quite understand what that meant. He came to see me one rainy night in Whitechapel, to see if I could locate him. I didn’t know how to break it to him, his red nose with delicate red veins hinted at a man who liked Jack Daniels, I told him that the Grapevine said that Abu Sa’ad had been killed.

He stumbled, he woke up, his eyes watered up, his lips quivered for a moment. I wanted to give him a hug. I felt like a scumbag. But he didn’t let me hug him, he composed himself. He told me about the phone call. I explained what that meant.

“To Islamic State death means martyrdom. For them it’s good news”

“I don’t know what to tell his mother” he said as if Flamur was still alive. “Is there anyway we can get Fatlum back? I need to tell him to come back? If we lose him, we are finished you know? Finished. I will not tell anything to the mother for now.”

A month later I called him to ask about Fatlum’s death.

Perhaps Flamur’s death made Fatlum want to join his brother, by this time he had lost Mohammed Nasser and now his brother. And so he stepped into a truck laden with explosives and stuck his index finger out for the camera and drove towards his target. He blew himself up hoping to be flung in to paradise. Whilst his friends in Islamic State rejoiced in his self-annihilation, the reverberations of the explosions were also felt in Ladbroke Grove. Friends and locals were shocked by the fate of such a popular young man. Some of the younger ones rated him for dying for his beliefs, “he was a man of action y’get me- he talks the talk and walks the walk.” To the old timers there is a sense of foreboding that the spotlight will once again fall on a community that is afflicted by far greater problems than ISIS.

[1] http://www.itv.com/news/2015-05-22/revealed-the-british-schoolboy-who-became-an-islamic-state-suicide-bomber/

[2] https://www.academia.edu/8689148/The_Radical_Nineties_Revisited_Jihadi_Discourses_in_Britain

[3] https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=lf1YAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA20&lpg=PA20&dq=british+moroccans+are+marginalised&source=bl&ots=I4vsPXJqsi&sig=V4s4EkLI-he1KF23UdMey7ZKG-c&hl=en&sa=X&ei=URqTVcCkNMa4UbfIgagF&ved=0CFIQ6AEwCQ#v=onepage&q=british%20moroccans%20are%20marginalised&f=false

[4] http://www.kcsc.org.uk/news/8-mar-2012-1448/golborne-ranked-second-most-deprived-ward-country

[5] Facebook post on 7 July 2002

[6] http://www.channel4.com/news/unmasked-the-man-behind-top-islamic-state-twitter-account-shami-witness-mehdi

[7] http://www.channel4.com/news/iftikhar-jaman-syria-death-isis-jihad-british-portsmouth

[8] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2723659/ISIS-militants-seize-key-towns-villages-close-Syrian-border-Turkey.html

[9] http://eng.majalla.com/2014/02/article55248465

* Tam Hussein is an award winning investigative journalist and writer. He speaks five languages and holds an MA in Near and Middle Eastern Studies from the School of Oriental and African Studies. His work appears in the Guardian, New Statesman, New Internationalist, Sharq Al-Awsat, etc.

With marginalisation comes social problems. Drugs and criminality had always been a facet of Ladbroke Grove since the 90s. Golborne Road was the best place to pick up skunk and hash in West London. Anyone who grew up in the area knew that Ladbroke Grove had cornered the market. You could drive up in a car and some dealer would shake your hands drop the punk and walk off in his joggers. Any undercover would have a hard time finding this ghost disappear into the estates. But as time passed these men, coming mostly from the close knit Moroccan community, felt the impact of religion in their lives. Their parents were getting old and becoming increasingly devout. They started their own families in the area and with the profundity of having one’s own family they too began to consider the deeper meanings of life. “Once a man holds his own kids in his arms” said one, “he starts thinking about their future, you can’t help it. That’s just God’s way”. A few decades on and these same dealers who had shot the stuff to willing punters, were sporting beards and praying five times a day looking for ways to atone themselves. These men raised in the school of hard knocks found that Salafi-jihadism fitted their temperament just like perhaps a creative temperament might prefer a Sufi understanding of Islam.

With marginalisation comes social problems. Drugs and criminality had always been a facet of Ladbroke Grove since the 90s. Golborne Road was the best place to pick up skunk and hash in West London. Anyone who grew up in the area knew that Ladbroke Grove had cornered the market. You could drive up in a car and some dealer would shake your hands drop the punk and walk off in his joggers. Any undercover would have a hard time finding this ghost disappear into the estates. But as time passed these men, coming mostly from the close knit Moroccan community, felt the impact of religion in their lives. Their parents were getting old and becoming increasingly devout. They started their own families in the area and with the profundity of having one’s own family they too began to consider the deeper meanings of life. “Once a man holds his own kids in his arms” said one, “he starts thinking about their future, you can’t help it. That’s just God’s way”. A few decades on and these same dealers who had shot the stuff to willing punters, were sporting beards and praying five times a day looking for ways to atone themselves. These men raised in the school of hard knocks found that Salafi-jihadism fitted their temperament just like perhaps a creative temperament might prefer a Sufi understanding of Islam.

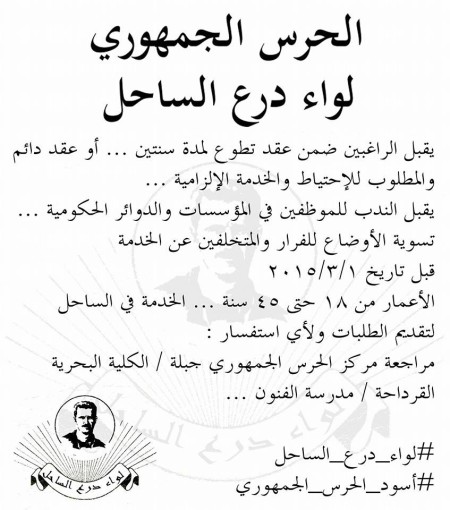

The Shadow Man of the Syria-Iran Axis

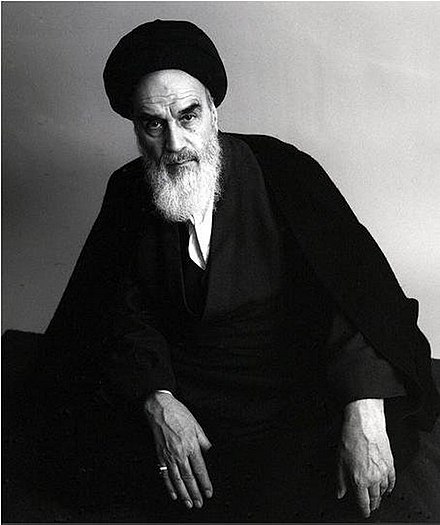

The Shadow Man of the Syria-Iran Axis Mohammad Nassif sensing that Syria could harness the Shiite awakening to its advantage became infatuated with Ayatolah Khomaini and Shia doctrine. His rapport and common intellectual outlook with Iran’s revolutionary clerics helped make him indispensible in Damascus, where secular Arabism seemed to preclude real sympathy with the Persian upstart. The secretive Major General was one of very few people, according to Patrick Seale, who could telephone Asad at any time of day or night. In the eyes of Iranians, he was not only a key channel to the Syrian President but also a power behind the throne.

Mohammad Nassif sensing that Syria could harness the Shiite awakening to its advantage became infatuated with Ayatolah Khomaini and Shia doctrine. His rapport and common intellectual outlook with Iran’s revolutionary clerics helped make him indispensible in Damascus, where secular Arabism seemed to preclude real sympathy with the Persian upstart. The secretive Major General was one of very few people, according to Patrick Seale, who could telephone Asad at any time of day or night. In the eyes of Iranians, he was not only a key channel to the Syrian President but also a power behind the throne.

The Syrian Southern Front: Why it Offers Better Justice and Hope than the Northern”

The Syrian Southern Front: Why it Offers Better Justice and Hope than the Northern”

The Iran-Syria Alliance: Sectarianism or Realpolitik?

The Iran-Syria Alliance: Sectarianism or Realpolitik?

All submissions should be sent to Charles Wilkins, Chair of the Prize Committee, at the following address:

All submissions should be sent to Charles Wilkins, Chair of the Prize Committee, at the following address: