Resolving Article 140: Settling the Issue of Iraq’s Disputed Territories Ahead of an Independence Referendum for Kurdistan

Posted by Matthew Barber on Thursday, July 13th, 2017

This article was published July 13, 2017 by NRT, a media service in Iraqi Kurdistan. The original article is available here. Photos and Images have been added to this re-post that were not present in the original.

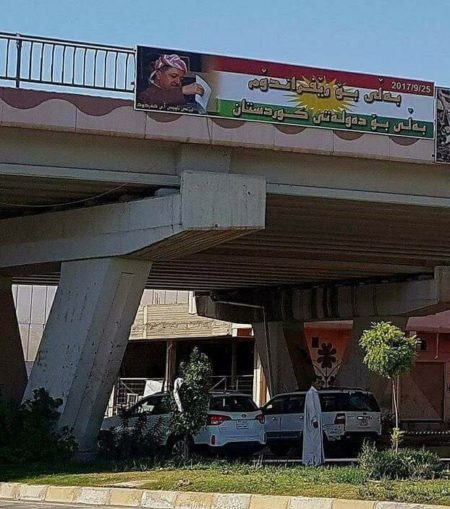

A new billboard in Erbil with Masoud Barzani’s image reading: “YES—for Kurdish independence and statehood”

by Megan Connelly and Matthew Barber

Contested Lands

Contested Lands

Last month, talks led by the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) at the presidential residence, Seri Resh, in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) led to a decision to hold a referendum this September on Kurdistani independence. Though the obvious assumption would be that only residents of the area seeking independence (i.e., the Kurdistan Region) would be able to vote on a decision to secede from Iraq, this referendum is being presented as a vote in which residents of Iraq’s disputed territories will also participate.

The disputed territories are areas in Iraq over which both the Iraqi Federal Government (IFG–based in Baghdad) and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG–based in Erbil) claim administrative rights. Currently, the Kurdistan Region is an autonomous jurisdictional entity that is part of a federal Iraq but which has its own government, armed forces, immigration laws, administrative bureaucracies, and so forth. Prior to any discussion of potential independence for the Kurdistan Region, it should be understood that the disputed territories are parts of the Nineveh, Salah ad-Din, Kirkuk, and Diyala governorates over which the respective governments of Baghdad and Erbil have been locked in conflict since the fall of Saddam Hussein. Even if the KRI was to not seek independence, the status of each disputed territory as a domain of the Federal Government or the Regional Government must be resolved. Kurdistani independence, therefore, involves more than the question of whether the inhabitants of the KRI desire independence; it also requires determining which disputed territories (all of which are outside of the official boundaries of the KRI) would be included in the KRI, and ultimately within the new independent state.

For years, the disputed territories have been exploited for their deposits of oil and natural gas, but have often been neglected amid a state of political and administrative limbo between Baghdad and Erbil. Many disputed territories have been under Kurdish military or administrative control following the US invasion of Iraq, even though services and infrastructure in many of these territories continue to be funded through the IFG budget. Now, as Kurdish security forces, Hashd al-Sha’bi, and other ethno-sectarian militias seek to consolidate their territorial gains with the liberation of the remaining Islamic State (IS) enclaves in the disputed territories, it is urgent the IFG and the KRG establish clear jurisdictional boundaries by peaceful means—to not do so could spell their eventual delineation in battle. Therefore, Erbil and Baghdad must revisit Article 140, the transitional provision of the Iraqi Constitution that mandates the normalization, census, and referendum processes that must occur to determine the future status of each disputed territory, individually. This will resolve whether the territories will become part of the KRI or will remain within the IFG’s system of governorates.

Why the Referendum Does Not Provide a Solution for the Disputed Territories

Acting KRG President Barzani has declared that the referendum will be a solution to the ongoing Article 140 dispute. But according to Hemin Hawrami, Senior Advisor to the acting president, the sole question that will be posed to voters in the referendum is: “Do you want an independent Kurdistan?”

No one disputes the fact that the vast majority of Kurds desire independence. One Kurdish researcher framed this observation as follows: “Kurdistan does not need a referendum because the history and geography and 100 years of struggle have answered this question for the whole world.” The referendum’s question, therefore, would seem almost superfluous for the KRI. But while the referendum’s proposed question may nevertheless be appropriate to direct at residents of the KRI, it is a premature question for inhabitants of the disputed territories. Whether or not voters want independence is not a relevant inquiry as regards the complex geographic, demographic, and political realities in the disputed territories, where the question that should be posed is: “Do you want your district to become a part of the Kurdistan Region?”

The idea that populations living outside of the Kurdistan Region could participate alongside residents of the KRI in a vote that would establish a basis for the statehood of a region whose future borders are not yet determined is simply confusing for Kurds, Iraqis, and outside observers alike. It is clear that at least two questions—not one—must be answered by separate groups of Iraqis.

Manipulating Patriotism

The phrasing of the referendum’s question is indicative of ethnic outbidding. By asking voters if they “want independence,” as opposed to inquiring, for example, as to whether voters approve of a parliamentary motion to declare independence, the KDP is playing a semantics game designed to force voters to deliver a “patriotic” or “unpatriotic” response, a tactic to rally broad nationalist support behind the KDP’s drive for political dominance while discrediting the domestic opposition by casting doubt on their supporters’ kurdayeti.

Beyond the realm of mere words, Kurdish authorities have already begun arresting dissenters and shutting down media centers that publish literature that “uses inappropriate language in connection with the referendum,” as well as harassing and assaulting journalists and writers who have expressed opposition to the referendum.

To garner support for the vote, the Kurdish nationalist parties—and the KDP in particular—have been aggressively fueling Kurdish irredentist sentiments and issuing provocative statements, such as KRG PM Nechirvan Barzani’s affirmation that the “disputed territories are no longer disputed,” the acting president’s assertion that opposition to the referendum would be met with a “bloody war,” and a KDP MP’s call for the legal prosecution and punishment of the political opposition to the vote. Moreover, the KDP has linked issue of Kurdish statehood with that of Masoud Barzani’s continued leadership and his defiance of Parliament’s attempts to limit presidential power. The alarming tone of this discourse rose to a crescendo this week when Barzani, before the European Parliament, accused opposition MPs of concocting an “attempted coupt d’etat” against him in Parliament prior to its dissolution by the KDP, and of being responsible for the deaths of children in the 2015 riots in the Sulaimaniyah Governorate.

Furthermore, the language of the referendum announcement itself does not acknowledge that disputed territories are “disputed,” instead referring to them as “Kurdish areas outside of the KRG’s administrative area.” This language does not recognize the presence of the very populations whose existence is the origin of the disputed territory dilemma: Arabs, Assyrian and Chaldean Christians, Turkoman, certain Yazidis who do not identify as Kurds, and others.

In addition to validating aggression against Kurdish domestic opposition, this kind of antagonistic, nationalist campaign will do nothing to assuage the fears and mistrust of minorities and non-Kurdish populations with competing claims to self-determination in the disputed areas. This could ultimately provoke violent reactions with armed sectarian and partisan militias, with their various regional sponsors poised to intervene.

Ahead of Referendum, Yazidis Targeted for Supporting Baghdad

In the last few years, observers have become increasingly familiar with how intimidation is employed to pressure minority populations of the disputed territories into political submission. Recent punitive measures against Yazidis who favor IFG rather than KRG administration for Shingal (Sinjar in Arabic) are a characteristic—and unsurprising—case in point.

A new Human Rights Watch report has this week exposed a tactic that the KDP asaish are using to deter Yazidis from aligning with Baghdad: expelling displaced Yazidi families from the IDP camps in Dohuk and evicting them from the KRI, if a family member joins the Baghdad-supported Hashd al-Sha’bi forces in Shingal. This tactic is unsurprising, as the KDP asaish already expelled (from the same camps in 2015-2016) displaced Yazidi families if a family member joined the PKK-affiliated YB?, a local Yazidi force in Shingal that challenges KDP hegemony.

A new Human Rights Watch report has this week exposed a tactic that the KDP asaish are using to deter Yazidis from aligning with Baghdad: expelling displaced Yazidi families from the IDP camps in Dohuk and evicting them from the KRI, if a family member joins the Baghdad-supported Hashd al-Sha’bi forces in Shingal. This tactic is unsurprising, as the KDP asaish already expelled (from the same camps in 2015-2016) displaced Yazidi families if a family member joined the PKK-affiliated YB?, a local Yazidi force in Shingal that challenges KDP hegemony.

The Yazidis of Shingal are a perfect example of the challenge of Iraq’s disputed territories. This population has long stymied KDP attempts to smoothly incorporate Shingal into the KRI. Yazidis are independently-minded, have repeatedly been victimized by external parties vying for control of their areas, and as a result are mixed as to whether they even identify as Kurds. Unlike Yazidis from villages inside the KRI, many Yazidis from Shingal resolutely identify only as “Yazidi,” maintaining that it is not only their religious affiliation but also their ethnic identity. The vast majority resent Kurdish politics and would prefer a quiet form of local governance. This hasn’t stopped the KDP from insisting that Shingal’s population wants to be included in the KRI, and they always have an array of token Yazidi mouthpieces ready to authenticate this claim.

The displacement of the majority of Shingal’s Yazidi population to the KRI during the Yazidi Genocide stirred fears among much of the community that they could be subjected to attempts to be resettled in the KRI rather than helped to return to Shingal and rebuild their lives. A KDP-enforced economic blockade of Shingal (implemented all of 2016 and early 2017) deliberately slowed the returns of Yazidi IDPs to Shingal. One motivation for this measure appears to have been to try to starve the YB? of resources and prevent a larger civilian support base for the YB? from growing in Shingal. Despite this measure to inhibit civilian returns, the KDP did not hesitate to evict families from the camps and return them to Shingal when their family members joined the YB?. Though many families wanted to return and rebuild in areas that had been freed from IS, other families were not yet ready to do so, and this punitive measure placed pressure on families to beg their young people to not join those forces.

For about two years, the KDP has branded the PKK affiliates as “foreign” entities, not acknowledging that their rank and file are comprised of local, Shingali Yazidis. The “foreign” argument is even less applicable to the Hashd al-Sha’bi: Yazidis are effectively being criminalized for the choice to work with their own federal government. Nevertheless, the asaish’s current expulsions follow the same pattern as the earlier YB? evictions: Though Yazidi families ultimately hope to return to a secure Shingal, many are not ready to leave the camps—for economic reasons as well as out of concern regarding the now three-way political standoff in Shingal. Targeting vulnerable families with forced evictions is therefore a powerful political deterrent.

Shingal is now divided by three political competitors, each having its own Yazidi militias on the ground: KDP-affiliated Peshmerga, PKK-affiliated YB?, and the Baghdad-affiliated Hashd al-Sha’bi. Two out of these three factions (with their associated civilian supporters) obviously do not favor inclusion into a KDP-dominated KRI. Most of Shingal’s Yazidis, therefore, do not oppose Kurdistani independence, but simply view it as none of their concern since they hope to administer Shingal locally and separately from the KRI. This should adequately illustrate how a single-question referendum on Kurdistani independence is entirely incapable of resolving disputed territory issues.

Practical Problems with Holding the Referendum in Disputed Territories

The proposed date of September 25, 2017 for the referendum initially gave the KRG less than four months to raise and allocate money, resources, and personnel to ensure that residents of the disputed territories would be represented. Facilitating the participation of people from the disputed territories will be extremely difficult, and quite costly, due to high rates of internal displacement. So far, only $6 million have been ear-marked for the referendum and the KRG can expect no financial support from its neighbors and international supporters, virtually all of whom have come out against the referendum. Even Turkey, one of the closest allies of the KDP, has spoken out strongly against the referendum. Additionally, none of the KRG’s international partners or the United Nations have thus far expressed a willingness to monitor the referendum. In fact, the United Nations recently issued a statement emphasizing that it “has no intention to be engaged in any way or form” in monitoring the independence referendum due to its commitments to the territorial integrity of Iraq. Therefore, aside from repeated assurances from Erbil that the process will be fair to ethno-religious minorities in the disputed territories, the KRI has not announced any plan to accommodate them or hold separate referenda on their preferences.

Rudaw has recently reported that as of yet, no preparations have been made for the referendum in Kirkuk, the most populated of all disputed territories. Typically, funding for elections would come from the Independent High Electoral Commission of Iraq (IHEC), but the Commission’s Kirkuk office has denied that it has a budget or a plan for the referendum. Since the referendum was initiated unilaterally, not through mutual discussion with Baghdad, the KRG cannot expect to receive support for the referendum from the IFG. The President of the Kirkuk Provincial Council, Rebwar Talabani, has proposed that Kirkuk prepare on its own for the referendum without relying on funding from the IHEC, but with just another two and a half months to prepare, there has been no consensus in the Provincial Council on how the referendum should be funded, or even regarding the legality of holding the referendum in the province.

Holding the vote for the people of Shingal could be even more difficult. Shingal’s Yazidis are now divided among the many thousands in the IDP camps of Dohuk; thousands more in IDP camps in Syria and Turkey; tens of thousands of recent migrants to Europe (most of whom would prefer to return to a secure Shingal); others who have migrated to Canada, the US, and Australia; IDPs in camps on Shingal Mountain administered by PKK-affiliated institutions; returnees to damaged/destroyed areas in KDP-administered areas north of Shingal; returnees to Yazidi villages south of Shingal now under the control of Hashd al-Sha’bi. What is the KRG’s plan to make sure that all of these people are able to freely and fairly vote in the referendum?

Mahama Khalil, unelected mayor of Shingal (Sinjar)—Photo: Kirkuk Now

In a recent interview with Kirkuk Now, Mahama Khalil (appointed by the KDP to act as unelected mayor of the Shingal District) also said that no preparations had been made to conduct the vote in Shingal. In the interview, he also exhibits a certain confusion as to the proper legal channels through which to conduct the vote and stated defiantly that the PKK and Hashd al-Sha’bi will not be able to disrupt the freedom of Yazidis to vote in the referendum. But the real question should be: What will guarantee that the KDP does not apply pressure on the voters? If the KRG intends to facilitate the Shingali people’s free, democratic decision as to the future of their district, things are off to a bad start with their asaish already punishing and intimidating those who express a desire to see Shingal remain under Baghdad’s administration.

Opposition to the Referendum within the KRI

Beyond the anticipated debacle of trying to hold the referendum in the disputed territories, the Kurdish mainland may also temper the success of the referendum. Though the vast majority of Kurds support the principle of Kurdish independence, there is significant anxiety among many in the KRI as to whether this referendum is being pursued in the right way and for the right reasons.

Contrary to assertions that this referendum has the backing of a broad political coalition, this has not been the case. The June 7 meeting at Seri Resh that resulted in the decision to hold the referendum did not include Gorran or the Kurdistan Islamic Group. The Gorran-led political opposition regards the referendum as a vote on the legitimacy of the KDP’s monopolization of power, Masoud Barzani’s unilaterally-extended presidency, and the abandonment of parliamentary democracy. Their sense is that the referendum would effectively make the KDP the vanguard of the nationalist movement and discredit the opposition, which insists upon institution-building or at least having working democratic institutions prior to statehood. Together, Gorran and the Kurdistan Islamic Group constitute 25% of Parliament. The Kurdistan Islamic Union has also announced its refusal to back the vote without parliamentary approval.

Billboards and signs associating Barzani’s presidency with independence now appear everywhere in Erbil

It is also unclear the degree to which the PUK supports the referendum. Despite the participation of PUK Leadership Council members in the Seri Resh conference on June 7th, the issue of holding an independence referendum has divided the PUK. In general, the PUK supports the reactivation of Parliament prior to holding an independence referendum. However, while some have backed the KDP’s proposal to reactivate the legislature with the current Speaker, Dr. Yusuf Muhammad, for one session, thirty-four out of fifty-five PUK Leadership Council members support[1] not just reactivation, but “normalization”—i.e. Gorran’s argument that Parliament must be reactivated and remain active until the next parliamentary elections (with Dr. Yusuf as Speaker)—and oppose the nomination of a PUK delegate to the Referendum Committee prior to Parliament’s reactivation. KRG Vice-Prime Minister Qubad Talabani and Kirkuk Governor Najmaddin Karim’s attendance—in defiance of the wishes of the majority of the Leadership Council—at the Referendum Committee hearings and at the KRG’s delegation to the European Parliament this week (to garner support for the referendum) prompted outrage within the PUK politburo. Mahmoud Sangawi, a member of the Leadership Council and General Commander of the Germian Region, lashed out at Talabani and Karim: “They are not representatives of the PUK. They represent only themselves.”

Is the Referendum Actually Binding?

While acting President Masoud Barzani has promised that the referendum on independence would be “binding,” Barzani and others, including KDP executive and former Iraqi Foreign Minister Hoshyar Zebari, have qualified this by saying that independence will not be declared immediately after the vote, but rather that the vote would give the KRG a mandate to open independence negotiations with Baghdad.

In fact, it is doubtful that the KRI would benefit politically or financially from declaring independence. With a budget shortfall of over $25 billion, the KRI has had extreme difficulty paying public salaries and pensions, providing services, and maintaining infrastructure in its administrative areas. A declaration of independence would mean that the KRI would not only be responsible for providing salaries to KRI employees, but also for public servants that are currently paid by the IFG, as well as providing utilities, water, and other services to the disputed territories. The KRI’s Ministry of Natural Resources, along with the provinces of Kirkuk, Nineveh, and Salah ad-Din also have production-sharing agreements (PSAs) with the IFG to extract and market Kirkuk crude that provide for significant infrastructure development in the disputed territories, the salaries of KRI civil servants, and healthy dividends for KDP- and PUK-linked production and marketing firms and the KDP-led Ministry of Natural Resources. Moreover, the announcement on the referendum came less than two weeks after the KRG Central Bank announced that it agreed to be taken over by the Iraqi Central Bank and the Iraqi Oil Ministry announced plans to finance the construction of a new oil refinery in Kirkuk to the tune of $5 billion.

With all of the above in mind, it seems that participating parties in the Referendum Committee are more interested in gaining leverage against the IFG and their domestic political rivals, and in maximizing the political and financial gains of the KRI’s two dominant parties (the KDP and PUK).

Whether the KRG actually intends to declare independence or not, the referendum campaign itself could nevertheless stir violent tensions among the various populations and political factions contending for the disputed territories. The referendum’s lack of planning, preparation, legal definition, or multilateral participation sets a dangerous precedent and may also be perceived as anticlimactic by many Kurds who have long struggled for independence.

The Solution

To ensure the stability and security of Iraq and Kurdistan, both the Federal and Regional governments must revisit Article 140 and make a concerted effort to determine once and for all the status of the disputed territories. Of course, implementation will be even more difficult now than it was twelve years ago, mainly because demographic normalization (which must precede the execution of a census and referendum) has been disturbed by population displacements in the wake of the IS invasion. With so much at stake and so many competing territorial claims to evaluate and negotiate, it will be extremely difficult for two governments that doubt each other’s good faith to commit to this long and arduous process. Yet, continuing to avoid the Article 140 process, as the pressure continues to build on all sides, will yield severe consequences for both governments as well as for their international allies.

Most analysts agree that the international community, particularly the United Nations and the United States, must step up its involvement in order to help stabilize Iraq’s post-IS landscape and adopt a framework to address the challenges posed by the jurisdictional conflicts in the disputed territories. Currently, the United Nations Assistance Mission to Iraq (UNAMI)’s mandate is limited to humanitarian and diplomatic assistance at the request of the Government of Iraq. Furthermore, the mandate’s scope is overly-broad, expressing the UN’s intention to promote economic and institutional development throughout Iraq, but without any clear focus on addressing the territorial disputes between the KRG and the IFG. Therefore, the UN will need a mandate specifically tailored to the mediation of the Article 140 process that will provide for the necessary resources for resolving territorial and property disputes and completing the normalization (or de-Arabization) process, conducting censuses, and referenda.

More than simply revisiting Article 140, the mandate must also address the effects of civil war, population displacements, and genocide that have occurred since the passage of the Iraqi Constitution. It will be necessary to secure KRG and IFG cooperation to reconstruct and provide adequate services to recently liberated cities like Shingal and Jalawla. It should also bring community leaders, regional and federal officials together to respond to the requests of small, territorially concentrated ethnic minorities for local administrative autonomy. Finally, but most importantly, the mandate should include the deployment of armed peacekeepers to prevent the eruption of clashes that could sabotage progress on the diplomatic and humanitarian end. Indeed, research has shown that multi-faceted missions (those that include diplomatic, humanitarian, and security provisions) are more likely to have successful, long-term outcomes than missions with a purely humanitarian or security focus.[2]

Although such a mission will depend on the KRG’s withdrawal of the present referendum proposal, independence for the KRI should not be off the table. Iraqi PM Haider al-Abadi has even conceded that the Kurds have a right to self-determination, up to and including their own state. However, if the Kurdish parties truly intend to secede from Iraq, the UN and Iraq’s international partners should condition their support for the independence process on the KRG’s commitment to the peaceful resolution of territorial, energy, and water disputes with the IFG, as well as its observance of the Region’s own laws and the authority of its own legally established Regional decision-making bodies. For example, the UN should require that the KRG reactivate its Parliament, hold legislative and presidential elections, and encourage the passage of a motion in Parliament authorizing the formation of a high committee to plan an independence referendum before it agrees to monitor the vote. Likewise, by obtaining guarantees from the international community to support a future independence referendum that is conducted in accordance with the above conditions, Barzani could save face domestically while withdrawing the current referendum.

Although UN peacekeeping missions do not have a stellar success rate, this can be partly attributed to the difficulty of the missions that the UN accepts, the lack of willingness on the part of host nations to give the UN the flexibility it needs to succeed, and a lack of cooperation from regional and international partners. While resolving territorial disputes will invariably be a grueling process, a mission to carry out Article 140 can still succeed if domestic, regional, and international partners are committed to it. Of course, a UN peacekeeping mission would be a bitter pill to swallow for both Baghdad and Erbil. It will be costly, it will require a long-term commitment, and parties will have to accept compromises that they may perceive as sub-optimal. Ultimately, the value of peace for both sides will outweigh the value of the benefits that either side would expect to gain from continuing down the current path, which will inevitably lead to armed conflict, whether by design or miscalculation. The diplomatic efforts of Iraq’s neighbors and international partners, particularly the US, will be crucial in raising the IFG and KRI’s perceived costs of noncompliance (such as threatening a withdrawal of military or financial support from the KRG and/or IFG) and reducing their perceived costs of compromise by offering incentives for both to accept UN conditions. Additionally, US influence will be necessary to secure the resolution from the Security Council to authorize a multi-faceted peacekeeping mission in the disputed territories.

Conversely, the UN must obtain guarantees of cooperation from the potential regional spoilers Iran and Turkey, as well as the United States. This will also require mutual assurances and recognition that a peaceful resolution of the Article 140 disputes is the optimal outcome and that all parties will commit their resources to that end. However, with the Iranian-backed Hashd al- Sha’bi making gains along the Syrian border and the mobilization of Turkish armed forces in the KRI (as well as Turkish air strikes against PKK and YB? positions in Shingal), regional actors appear to be on a war footing in Iraq. So is the US. With a weakened Department of State, a newly-empowered Pentagon, and an Ambassador to the UN who recently bragged about cutting the peacekeeping budget by over half a billion dollars, hope of US support for peacemaking in Iraq may prove illusory as well.

—

Megan Connelly is a PhD candidate with the Department of Political Science at SUNY University at Buffalo, concentrating in civil war, peace-building, and power-sharing studies with a focus on the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. She can be followed on Twitter: @meganconnelly48

Matthew Barber is a PhD student studying Islamic thought and history in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago, who has conducted research on the Yazidi minority. He was working in Kurdistan when the Yazidi Genocide began and later led humanitarian and advocacy projects in the country for one year (2015-2016). He can be followed on Twitter: @Matthew__Barber

[1] The PUK concluded an agreement with Gorran in May of 2016 to, among other things, form a joint Leadership Council and electoral list and prioritize the reactivation of Parliament and the enactment of political and economic reforms. Gorran has since accused the PUK of violating the agreement because it has continued to negotiate political and natural resource agreements secretly with the KDP politburo.

[2] Hultman, L., et al. (2014). “Beyond keeping peace: United Nations effectiveness in the midst of fighting.” American political science review 108(4): 737-753. Beardsley, K., et al. (2017). “Resolving civil wars before they start: The UN security council and conflict prevention in self-determination disputes.” British journal of political science 47(3): 675-697.

Discover more from Syria Comment

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Comments (2)

ALAN said:

A look, from outside of Mr. Matthew”s focus

Quote from the Voltaire Network:

Washington and Moscow would allow Turks to sort out their differences with the Kurds, in other words, to massacre them /Where the interests of the big players are consistent/. Exactly the way in which Henry Kissinger supported the Iraqi Kurds against Saddam Hussein, before abandoning them overnight with their dream of a Kurdistan.

the Kurds will pay for their mistake of having fought outside of their territory as proxy fighters

July 14th, 2017, 1:04 pm

ALAN said:

a violent downward spiral? any potential torsion field now with kurdish issue?…… America is in its way providing an equal amount of negative energies in the so called “Kurdistan” isimultaneously …… They know that a violent thunderstorm could be unleashed at any moment.? It’s a theory of TORA-SION fields.

July 15th, 2017, 6:32 am

Post a comment