Israel’s Secret war for Syria’s Independence by Meir Zamir

Posted by Chris Solomon on Wednesday, June 20th, 2018

Israel’s Secret war for Syria’s Independence

By Meir Zamir

(First published in Haaretz newspaper, June 15, 2018)

At the end of the War of Independence, Israel faced a policy dilemma with regard to Syria. The armed confrontation on the border around the demilitarized zones and over the draining of Lake Hula was continuing, and Syria still claimed the waters of Lake Kinneret. At the same time, Israel acted to foil an Anglo-Iraqi plot to seize control of Syria. Documents found in Israeli and French archives reveal new details about Israel’s secret policy at the time to ensure Syria’s sovereignty, a policy that could perhaps affords insights for the present period as well.

During 1949, Syria was rocked by three military coups which put an end to the democratic-republican regime and heralded the age of rule by army officers both there and in other countries in the region. The three coups – led, respectively, by the chief of staff, Husni Za’im, on March 30; by Sami al-Hinnawi, on August 14; and by Adib Shishakli, on December 19 – were a direct result of Syria’s failure in its war against Israel, aggravated by the acute economic crisis that broke out in the wake of the military debacle.

Compounding these crises were subversive efforts fomented by the Hashemite regimes in Jordan and Iraq. King Abdullah of Jordan viewed the establishment of “Greater Syria” as the summit of his geopolitical yearnings; and, in Iraq, the regent, Abd al-Ilah, and the prime minister, Nuri Sa’id, each of whom sought, for his own motives, to effect an Iraqi takeover of Syria, whether by means of unification or federation. The military coups signaled the start of years of struggle over Syria; the country became an arena of regional and great-power strife, which persisted until Hafez Assad’s coup in 1970.

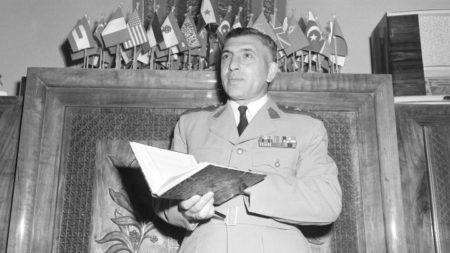

Nuri Sa’id

In contrast to the policy of the present Israeli government, which has advocated nonintervention in the civil war in Syria, the government headed by David Ben-Gurion viewed a British-backed Iraqi takeover of Syria as a direct threat, and took clandestine measures to foil it. A year after the end of its war against the Arab states, Israel, now a full-fledged state of its own, tried to influence the regional order on the basis of its interests. By means of an astute use of intelligence material and secret diplomacy, Ben-Gurion and Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett were able to radically revise Israel-Syria relations: Israel went from being a threatening force that Iraq and its supporters invoked as a pretext for military intervention allegedly intended to protect Syria, to a regional power whose very threat to intervene averted an infringement of Syria’s independence and sovereignty. Israel’s support for Syria as an independent state, against Iraq’s subversive efforts there, also created a basis for cooperation with King Faruq of Egypt and King Ibn Saud in Saudi Arabia.

The Iraqi threat

The origins of Ben-Gurion’s opposition to Iraqi influence lay in the pre-state period. In July 1947, French sources passed on to Ben-Gurion, then head of the Jewish Agency, information suggesting the existence of Anglo-Iraqi collusion, by which senior British officers in Cairo and Baghdad, in coordination with Nuri Sa’id, the Iraqi strongman, were acting to escalate Jewish-Arab tensions to the point of a full-scale war. The alleged scheme aimed not only to prevent the creation of a Jewish state – or, at least, one whose territory did not extend beyond the coastal plain – but also to ensure the support of Arab public opinion for an Anglo-Iraqi defense pact, and at the same time to use a Jewish-Arab war as reason for an Iraqi military invasion of Syria.

Ben-Gurion

Ben-Gurion attached great importance to this information, and at the beginning September 1947, in the midst of the preparations of the Yishuv – the pre-1948 Jewish community in British Mandate Palestine – for war, paid a visit to Paris to confirm it. Already in the French capital were the officials who managed the intelligence contacts with France: Ben-Gurion’s Arab affairs adviser, Eliahu Sasson, and the Jewish Agency representative in Paris, Maurice Fischer.

Ben-Gurion viewed Iraq and its leader, Nuri Sa’id, as a major threat in Israel’s anticipated war with the Arab states. Not only was Iraq the spearhead of an extremely bellicose approach in Arab League meetings toward the end of 1947; Sa’id was also working, in collaboration with the British, to promote a plan for a binational state in Palestine to supplant the partition plan.

Ben-Gurion’s apprehensions were well-founded: Iraq possessed considerable economic resources, along with large ground forces and air power. Furthermore, in the Anglo-Iraqi defense treaty (the Portsmouth agreement) of January 1948, the British promised to arm Iraq’s forces and transform them into a modern army.

French agents and their opposites in the Jewish Agency’s political department set out to thwart the Anglo-American scheme. French sources leaked the details of the plot to Syrian President Shukri al-Quwatli and to the Egyptian and Saudi monarchs. Eliahu Sasson passed on details of the conspiracy to King Abdullah, who strongly opposed an Iraqi takeover of Syria.

The Anglo-Iraqi move failed due to the counter-activity of a coalition that included the Soviet Union, which operated through the Iraqi Communist Party, and King Ibn Saud, of Saudi Arabia, who was aided by the anti-British Iraqi leader Rashid al-Kailani. In the face of mass demonstrations and clashes with the police in Baghdad, in which protesters were killed and wounded, the Hashemite crown prince, Abd al-Ilah, was compelled to retract the ratification of the defense treaty with Britain. Although an Iraqi expeditionary force took part in the war against Israel, the failure of both the Portsmouth agreement, and in its wake of the Anglo-Iraqi conspiracy, went a long way toward reducing the Iraqi military threat to Israel. Indeed, in September 1948, Nuri Sa’id published a memorandum concerning the negotiations on the Portsmouth treaty with Britain, in which he argued that the cost exacted from the Arabs for the undermining of the agreement was the loss of Palestine.

After the failure of the efforts to prevent the establishment of a Jewish state or to reduce its size, Sa’id, again with the aid of British agents, tried to obtain, through military pressure and diplomatic means, what had not been achieved through war. In the second half of 1948 and during 1949, the Iraqi leader intensified his anti-Israeli activity. In talks with other Arab leaders, he urged opposition to any negotiations on an armistice or a peace treaty with Israel, and demanded that preparations be made for a second round of hostilities. He also supported the plan of the United Nations mediator Folke Bernadotte and, like the British, tried to get the Negev severed from Israel.

The Iraqi expeditionary force, which consisted of two brigades that had been involved in the fighting on the central front in Samaria, constituted an additional means to threaten Israel. Even though the Iraqi forces were not involved in offensive action after July 1948, their presence was an important factor in Ben-Gurion’s position during the war regarding Israel’s future borders. In the second half of 1948, the Iraqi expeditionary force was significantly beefed up in arms and manpower, and stood at four reinforced brigades with an armored force and an air force squadron that was located in Jordanian airfields. Thus, in the negotiations for a cease-fire and the future of the West Bank, Israel demanded that King Abdullah pull back Iraqi forces to the east of the Jordan River. Iraq itself refused to have any contact with Israel, and only after the signing of the Israeli-Jordanian armistice agreement, on April 3, 1949, did its forces withdraw to northern Jordan, thus posing a direct threat to Syria. Both the Syrian president and the Israeli prime minister saw this as the second stage of the Anglo-Iraqi plot of July 1947.

Black-market diplomacy

Ben-Gurion’s determination to undercut the British in Syria stemmed from his belief that their influence in Damascus would endanger Israel, and that behind its designs were the same intelligence, army and Foreign Office circles that had tried to block Israel’s creation, encouraged the Arab leaders to go to war against Israel, and tried to reduce its territory. As Sasson warned in a meeting in December 1949, “We have an enemy that is far stronger than the Arabs – the British.”

The same view was espoused by many at the French Foreign Ministry, as well as in the French military and intelligence. They joined with Israel in an effort to block Anglo-Iraqi domination of Syria. A French diplomat who was well acquainted with British clandestine activity in the Middle East, and particularly in Syria, labeled it “black market diplomacy” – namely: In tandem with the official policy pursued by Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, which prioritized British-French relations (in December 1945, Bevin had signed an agreement in which Britain recognized France’s special status in Syria and Lebanon), other elements in London, as well as in the Middle East, were acting to undermine France’s position in the latter region and in North Africa. Following the coup staged by the pro-Iraqi Sami al-Hinnawi in Syria, and the murder of Husni Za’im, Le Monde, which reflected the views of the Quai d’Orsay, accused the “gang of Stirling, Ferar, Spears and Glubb and their ilk” (British diplomats and Arabist intelligence and military officers) of responsibility for the coup.

Indeed, the Syrian documents and British intelligence papers that I located in French archives(See annexed documents) contain numerous testimonies about Nuri Sa’id’s clandestine collaboration with Arabists from British intelligence to engineer an Iraqi takeover of Syria. From the British perspective, the villain of the piece in Syria was President Quwatli, who had retracted secret understandings with British agents by which they would help him get elected president and get rid of the French, in return for which he would recognize Britain’s strategic and economic interests in Syria and agree to have his country join an Iraqi-led Hashemite federation. The British upheld their end of the bargain, but Quwatli now claimed that, with Syrian independence assured, there was no place to trade one colonial regime (French) for another (British).

The Syrian public wholeheartedly supported the country’s newly won independence, following their war of liberation against France, and opposed unity with the Hashemites, whether Iraq or Jordan, which would entail the extension of British influence over their country. Quwatli’s struggle for an independent Syria also had strong support from Egypt and Saudi Arabia, from the United States and, behind the scenes, from France, too.

British circles in the Middle East disagreed about how their country’s goals should be achieved in Syria. Among the personnel of the British intelligence center in Baghdad – the second largest in the region, after Cairo – there was considerable support for unification or federation between Iraq and Syria as a means to ensure the stability of the Hashemite regime in Iraq, and they actively assisted Iraqi subversion in Syria. However, the intelligence and military circles in Cairo maintained that Syria could remain an independent state, on condition that its leaders sign a defense treaty with Britain and join a regional defense alliance against the Soviet Union.

The escalation of the Cold War during 1948-1949 heightened the pressure on British representatives in the Middle East to ensure the consent of the Syrian government to become part of the regional defense alignment. On January 19, 1949, the British ambassador in Damascus submitted a memorandum to Quwatli, offering the president British recognition of his country’s independence and sovereignty in return for a defense pact. A copy of the memorandum was made available to French intelligence through an agent in the Syrian Foreign Ministry and given to Sasson, who was in Paris at the time.

The Israeli-Kurdish connection

Jerusalem, too, toyed with the idea of provoking regime change in Syria. The idea, first broached in August 1948 by Ezra Danin, Arab affairs adviser in the Foreign Ministry, was not without its logic. In the months that followed, Israel received two requests from Syrian figures of Kurdish extraction for assistance in a seizure of power in Damascus. The first request came from Husni Barazi, who had been prime minister in Syria in the early 1940s, and afterward provided information to Shai, the intelligence service of the Haganah, Israel’s pre-state defense force. His idea was for Israel to foment tension on the border with Syria in order to force Damascus to mass troops on the front. This would enable Barazi to take Damascus with the aid of Kurdish and Druze troops, oust Quwatli and seize power. The second request, which came from the commander of the Syrian army, Husni Za’im, was more important, because a few months later Za’im staged the country’s first military coup, and seized power. Za’im, who was concerned he would be removed because of the army’s failures, also demanded financial assistance from Israel.

Husni Za’im

Reuven Shiloah, Ben-Gurion’s adviser on intelligence, had already warned British intelligence agents in February 1948 that the Zionist movement might support a Kurdish revolt if Britain continued to act against the establishment of the Jewish state. This was a warning not to be taken lightly, as in 1945 a Soviet-backed Kurdish revolt in northern Iraq had inflicted heavy losses on the Iraqi army. Indeed, from 1948 to 1952, Israel proffered aid to the Kurds in Iraq, primarily of a diplomatic and propaganda character, as a counterweight to the Iraqi involvement against Israel. Among other actions, Israeli representatives acted behind the scenes to get the Kurdish national claims placed on the agenda of the United Nations and its institutions, recruiting to that end American personalities, institutions and journalists. Now the suggestion was to assist a “Kurdish coup” in Syria, taking advantage of the prominent position of Kurdish figures in Syrian politics and the military.

The liaison to Barazi and Za’im was Kamuran Badr Khan, a central figure in the Kurdish national movement, who was in close touch with Maurice Fischer in Paris. The latter supported Badr Khan’s proposal, but Eliahu Sasson, who was conducting secret talks with Arab representatives at the time, was opposed; Israeli involvement in a coup in Syria was dependent on the allocation of the necessary resources, he said. Ben-Gurion and Sharett accepted his approach.

Two days after his coup, Za’im met with the French military attaché in Damascus and confirmed his country’s intention of preserving Syria’s independence in the face of the Hashemites and of Britain, and revealed that he intended to lead the Iraqi leaders astray in order to gain time to consolidate his rule. He also sent a calming message to Israel, through the French attaché, whom he told that he was confident that Israel would not allow the Hashemites to seize control in Syria, because it “doesn’t want the British as neighbors.” Za’im’s coup did not come as a surprise to Israel, though it was not initially known who was behind it. Nor was Israel worried by Nuri Sa’id’s visit to Damascus and his demand for a defense pact between the two countries against “the Zionist aggression.”

Toward the end of April it became clear that Za’im had adopted his predecessor’s policy, tightening Syria’s relations with Egypt and Saudi Arabia against the Hashemites in Iraq and in Jordan. He also took action against Britain and drew closer to France, which supported him militarily and economically.

Za’im’s confidence in his ability to withstand Anglo-Iraqi subversion derived above all from his close ties with the United States. That CIA agents in Damascus were involved in Za’im’s coup is known, but French sources add further details, according to which the coup was “bought” by the Aramco petroleum company. The American firm paid Za’im $20 million for the right to run Tapline, the pipeline that carried Saudi oil to the Mediterranean, through Syria.

Roadside murder

The direct relations of Za’im and his Kurdish prime minister, Muhsin al-Barazi, with Israel, and Zaim’s declaration of his readiness to make peace with Israel and to settle hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees in Syria, stirred outrage among British officials. Addressing a meeting in London of British representatives in the Middle East, senior Foreign Office personnel sharply criticized Israel. The country’s very existence, they said, was endangering the prevailing Arab regimes, as the Syrian case proved, and constituted a direct threat to Britain’s strategic interests in the Middle East.

Nonetheless, Foreign Secretary Bevin met with an Israeli diplomat in London on July 19, 1949, and conveyed to him a conciliatory message affirming Britain’s recognition of Israel along with London’s readiness to accept Israeli control of the Negev.

Israel pinned great hopes on Za’im, and worked clandestinely to ensure his rule. In the armistice negotiations, which had begun on April 5, 1949, the Syrians had adopted a tough posture, as part of Za’im’s effort to portray himself to the Syrian public as the country’s defender against Israel. Ben-Gurion played his part in the show by threatening to exercise force to impose Israel’s conditions on Syria. The prolongation of the talks was also influenced by French pressure on Israel aimed at ensuring an achievement for their ally. An armistice agreement between the countries was finally signed on July 20, 1949, the last of the accords in the wake of the war. At the beginning of August, Sasson suggested to Syrian Prime Minister Muhsin al-Barazi that he come to Damascus or that the two meet in Paris to discuss a peace agreement between the two countries – but it was already too late.

Israel’s sophisticated policy in Syria revealed itself in May-June 1949, when Iraq concentrated thousands of soldiers on its border with Syria as part of its efforts to depose Za’im. On May 21, the Israel Defense Forces received an order to prepare Operation Oren, ostensibly to oust Syrian forces from Mishmar Hayarden in Upper Galilee. In reality, the move was intended to deter the Iraqi forces from attacking Syria, with a warning message sent to Britain as well. The goal of the Israeli operation was defined as the conquest of the town of Quneitra, on the Golan Heights, which would pose a direct threat to Damascus. Together with the Syrian army, the Iraqi army and air force were also classified as an enemy to be fought should they intervene.

In parallel, Egyptian King Faruq promised Za’im to send dozens of warplanes to Syria in order to protect the country from an Iraqi offensive. Za’im, for his part, bolstered his forces on the Syrian border with Iraq and arrested the pro-Iraqi tribal leaders in the Jazira region of northeast Syria. He also asked France to supply arms to his forces urgently, and requested the Saudi king to mass troops on his country’s borders with Iraq and Jordan, in order to deter the Hashemite regimes from attacking Syria.

Although Iraq was in fact deterred from making direct use of its armed forces against Syria, Iraqi and British agents continued to scheme for Za’im’s removal. On August 4, Prime Minister Barazi uncovered details of a British-Iraqi plot to assassinate Za’im. The publication of the names of the British intelligence officers involved caused extreme embarrassment in Britain. An analysis of the patterns of behavior of Israeli intelligence in Syria during the months that followed raises the possibility that the information about the plot came from Israel. Nonetheless, 10 days later, British and Iraqi agents succeeded in organizing a military coup in Syria through a group of officers led by Sami al-Hinnawi. Za’im and Barazi were taken from their beds at midnight and shot on the road to Mezze, outside Damascus.

The assassination was welcomed in Iraq. Radio Baghdad declared joyfully that, “Two Kurds – Za’im and Barazi – have been removed for supporting French imperialism.” Responding to the French military attaché in Damascus, who was concerned about the repercussions of Hinnawi’s coup, his British counterpart stated that “Syrian-Iraqi unification will not be effected without Syrian support.”

Code-breaking as a policy tool

The British government’s official position was that it was not working to promote Iraqi-Syrian unification or federation, but would not stand in the way of the two countries if their elected representatives were to decide on this course of action. In practice, British agents assisted Iraqi representatives in Damascus with their efforts to ensure the victory of the unification camp. In a propaganda campaign launched in Syrian and Lebanese newspapers owned by Iraqis, and via radio broadcasts, unification with Iraq was presented as the step that would save Syria from anarchy and from an economic crisis, and would become a cornerstone in the struggle against both Israel and French imperialism.

However, both within Syria and outside, substantial forces operated to foil unification with Iraq. Army officers were again active in the opposition; many of them were Syrian patriots who advocated their country’s independence and were apprehensive of becoming a tool of the Iraqi army. King Ibn Saud led the campaign against Iraq’s activity in Syria, investing large sums of money in the effort. King Faruq and French agents were also very active.

The intensity of the resistance is reflected in an assassination attempt on Walter Stirling, supposedly the London Times correspondent in Damascus but actually the senior British intelligence figure in the Syrian capital.

Adib Shishakli

The opponents of Anglo-Iraqi control in Syria were ultimately successful. On December 19, Col. Adib Shishakli, of Kurdish descent, led a tank assault on Damascus and seized power in order to save Syria from British influence and avert unification with Iraq.

A number of signs suggest possible Israeli involvement in the coup, including a meeting between Shishakli and Israeli representatives ahead of the event. Either way, there is no doubt that once Shishakli seized power, Israel helped him consolidate his regime, as it had done with Za’im.

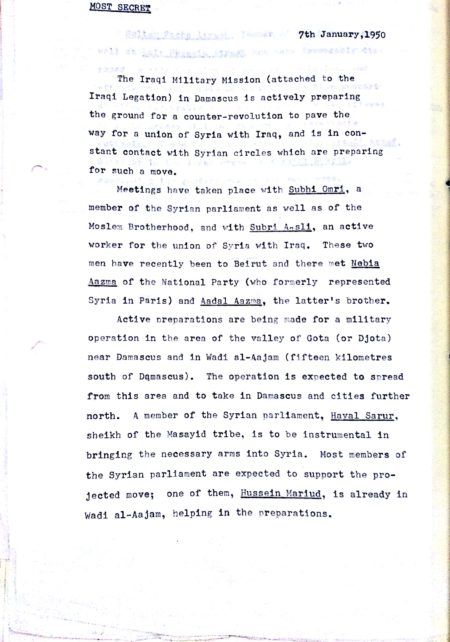

Israel possessed an extremely efficient tool to thwart Anglo-Iraqi subversion in Syria. Documents in Israel’s State Archives, which became available to researchers in the past few years, show that at the end of 1948 Israel began to decode encrypted messages between the Iraqi embassies in Damascus and London and the Iraqi Foreign Ministry, and between the Iraqi military delegation in Damascus and the Ministry of Defense in Baghdad. The military delegation, which had been formed in early 1948 as part of the Arab League’s coordination plans for the war against Israel, became Iraq’s primary means of subversion in Syria, particularly among the Syrian officer corps. The decoding of the Iraqi communications from London was an extremely important tool, as it shed light on Britain’s secret involvement not only in Syria but across the Middle East.

Information gleaned by Israel, some of which was conveyed to Adib Shishakli, from decoded communications between the Iraqi Embassy and its military mission in Damascus and Baghdad.

Even though Shishakli was an avowed foe of Israel – he had joined Fawzi al-Qawuqji’s Army of Salvation in the war against Israel, had commanded the Yarmouk Battalion, which entered Israel in January 1948 and was involved in hostilities in Galilee – Israel took steps to foil the Anglo-Iraqi plots against him. Information was passed to his representatives at the armistice talks about Iraq’s subversive activity, including about plots to murder him and his main supporter, Akram al-Hourani. In addition, the Israeli threat to intervene militarily in Syria in the event of an Iraqi attempt to take control there was a major deterrent factor in Anglo-Iraqi considerations. When a senior French diplomat complained to the British foreign secretary, Anthony Eden, in early 1952, about the Iraqi efforts to undermine the regime in Damascus, Eden claimed that Britain was neutral and noted Israel’s threats to intervene.

But Israel conducted a dual policy in the case of Shishakli, too. On the one hand, there were acute clashes with the Syrian army, even assecret talks were being held about settling hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees in Syria and signing a peace agreement with Damascus. Shishakli’s overthrow, in February 1954, with direct Iraqi and British involvement, put an end to the contacts. The Anglo-Iraqi subversion in Syria continued in the years that followed, led by Nuri Sa’id and revolving around the 1955 Baghdad Pact (formed by Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Turkey and the UK), but now American agents were also involved. In 1957, a joint MI6-CIA operation (“Operation Straggle”) to oust President Quwatli, who had returned to Syria from Egyptian exile in 1955, failed. This time, Israel, which was now collaborating with Britain against Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, did not intervene.

The obsession with Syria brought about the end of the monarchy in Iraq. In the wake of the Egyptian-Syrian union in 1958, and the pro-Nasser disturbances that broke out in Lebanon that year, Nuri Sa’id ordered a military force under the command of Abd al-Karim Qasem to move toward the Syria-Jordan border. Qasem took advantage of the passage of army units through Baghdad to mount a blood-drenched coup: The members of the royal family were murdered, and the body of Nuri Sa’id was dragged through the city’s streets before a cheering crowd.

Lessons for the present

Despite the time that has passed and the different circumstances, insights applicable to our time can be gleaned from Israel’s behavior vis-a-vis Syria in the 1940s and early 1950s. Amid the dynamic, fluid situation of the contemporary Middle East, Israel cannot adopt the position of a bystander when a serious vacuum appears in one of its neighboring countries, something that could pose a potential danger to Israel. Israel’s unilateral disengagements from South Lebanon and the Gaza Strip, in 2000 and 2005 respectively, may have had short-term tactical advantages but they created long-term strategic threats. The same applies to Israel’s fence-sitting with regard to the current civil war in Syria, which has allowed Iran to consolidate its influence in that country.

In the present Syrian crisis, Israel would do well to adopt Ben-Gurion’s policy: to support Syria as an independent, sovereign state, as it existed until the eruption of the civil in 2011. In this context, the assumption accepted by many scholars concerning the disintegration of the “failed Arab state” has proved premature. Both Lebanon and Iraq endured blood-drenched civil wars, and in both cases it was argued that they would fall apart because of their religious and sectorial compositions. Nevertheless, Lebanon and Iraq are succeeding in rehabilitating themselves as state frameworks and each is also beginning to buttress its national identity.

When it comes to Iranian subversion in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon, it’s worth remembering that there is a deeply rooted ethnic-identity conflict between “Arabs” and “Persians.” In the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s, many Shi’ite Arabs in Iraq demonstrated their loyalty to their homeland when they joined the Iraqi army and fought against Shi’ite Iran. To date, Iran has made effective use of the threats to the Muslim world of American imperialism and of Israelin order to bridge that conflict. However, the outcome of the recent election in Iraq, in which demonstrators in Baghdad chanted anti-Iranian slogans, indicates that a substantial portion of the Iraqi people, among them many Shi’ites, object to Iran’s political and economic influence in their country. Similarly, Hezbollah, precisely because of its achievements in the recent election in Lebanon, will find it difficult to act as an Iranian agent that will risk Lebanon’s destruction in an unwanted war against Israel.

It’s reasonable to assume that following the end of the civil war, Syria will undergo a similar process and rehabilitate itself as a state, while reconstructing its Syrian-Arab national identity. Syria’s leaders across the decades, including Hafez Assad, the father of the president Syrian leader, did not fight for their country’s independence against France, Britain, Iraq, Transjordan and even Egypt only to turn their country into a base of Iranian influence. Instead of threatening Bashar Assad, Israel should work to widen the gap between the Syrian regime, and above all the Syrian people, and Iran. Threats of the kind being voiced in Israel – to assassinate the Syrian president, or to “partition” Syria – certainly do not help.

Meir Zamir is emeritus professor of Middle East history at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. A new edition of his book “The Secret Anglo-French War in the Middle East: Intelligence and Decolonization, 1940-1948” was published by Routledge in 2016.

Document 1: End of February 1945 Jamil Mardam in Cairo informed President Quwatli of a quarrel between Nuri Sa’id and Yusuf Yasin, King’s Ibn Sa’ud’s adviser for Foreign Affairs

When Nuri Pasha arrived at Maher Pasha’s house he shook hands with everyone present, and when he reached Sheikh Yusuf, he said to him,

“Have your efforts been crowned with success?”

“What efforts are you talking about, Pasha?”

“When will you take Faisal al Saud to Damascus as king?”

“You are not serious,” answered Sheikh Yusuf.

“I am indeed,” said Nuri Said. “I think that the Syrians will pray to God for you many times.”

“May his name be praised”, replied Sheikh Yusuf.

At that moment Mr Zerkali) adviser to the Saudi monarch) intervened, saying,

“In reality, I do not understand the meaning of your words, Pasha. Faisal al Saud and all the Bani Saud in general, will only be able to have what God has granted them. You know that they only want the wellbeing of the Arabs and all Muslims in general.”

Nuri Pasha replied in anger,

“I hope that people are unsparing with their advice to you, now, sir. You are from Damascus, and I know the mentality of the Syrians as I have lived among them and seen them in Iraq. God is my witness, the Syrians have always sullied anything they have been involved in.”

Sheikh Yusuf, “Oh, excuse me, Pasha, excuse me.”

It seems that the Pasha was inclined to get into a fight. He said,

“What have you done and what has your king done?”

Mr Zerkali, “Our king is not the topic of our conversation now.”

“But he is,” replied Nuri Pasha, “He is the topic of our whole conversation. We can not remain silent, us Iraqis, about the actions we see and of which we hear. We have not come here to disperse Arabs, but to unite them. All the efforts you have put in since the start of our Conference have been designed to create obstacles for us or to spoil our work.”

Document 2:

Top Secret

From Mr. Camille Chamoun, Lebanese Minister in London

on a mission to Baghdad

to Jamil Mardam Bey, Syrian Minister of Foreign Affairs

Encoded

I saw the British ambassador here. The English do not oppose anything that could be useful for us. They won’t intervene if the Iraqi tribes try to provoke the French. However, the French cannot be provoked in the desert. Moreover, if the tribes find a real interest in the matter, they won’t fail to take action. The movements of the tribes are therefore not useful.

As for the Iraqi army, it is ready to take action; but the Iraqis are asking themselves what will be the result of this action. Some officers said to me:

“Do you support the unification of Syria and Iraq?”

The Iraqis believe that when leaving for Syria, they won’t retreat. Their goal is Damascus and nothing else.

In any event, it is preferable for us to be governed by the Iraqis that to end up again under the French yoke.

20 May 1945 S/ Camille Chamoun

Letter sent by Camille Chamoun through the British Embassy in Baghdad.

Author’s note: Camille Chamoun, later Lebanon’s president, was sent to Baghdad by British intelligence to help in organizing an Iraqi army invasion of Syria against the French.

Document 3:

King Ibn Sa’ud reprimands President Quwatli for not standing up to Nuri Sa’id and King Abdullah

Secret

Nuri al-Sa’id’s activities are beginning to take a serious turn. We are unable to allow Abdullah’s plots. By God, your attitude is strange. People are working for your death and you do not move. I learnt that in Damascus Abdullah’s propagandists are exerting themselves as much as possible. What are you waiting for? We know, as you do, who supports and controls them. Why don’t you speak? God has ordered us not to be quiet when it is a matter of right, and has called someone who does not speak out a demon.

I ask you to appreciate the gravity of the situation. The anarchy reigning with you weakens any hope of success and it is sad to see that it is spreading. Can you not find a way to settle the situation instead of letting these scandals develop? Your situation pains us. It was not like this under French rule. Someone who enjoys my confidence told me that people are beginning to miss the period of French rule. Do something before your edifice falls down.

9 Shawwal 1364 (September 15, 1945)

S/ Abd al-Aziz

Author’s note: King Ibn Sa’ud continued to play a central role in opposing a Hashemite takeover of Syria, and supported Husni Za’im and Adib Shishakli.

Document 4:

Nuri Sa’id to the Turkish President

Top secret

His Excellency President Ismet Inonu

The Iraqi government must, for the moment, despite its desire to see a royal Syrian government established and facing the possibility of seeing the problem of the government of the Syrian Republic in its current state resolved, study with a degree of reserve all the proposals you have made to it regarding the question of the Turkish-Syrian borders and particularly as far as the regions of Aleppo and Kameshli are concerned.

The greatest difficulty really rests with this claim you have made and which is the annexation of Aleppo to Turkey. But I can assure you, with authority and from now that your claim regarding the border at Kameshli can be accepted, so long as it does not exceed in depth the adjustments imposed on the borders from 70 [probably 1870], as regards fortified land in relation to the current borders.

So I must also now obtain an assurance that the lands for which you accept cession to Syria are the equivalent of lands you are demanding. And you will indicate the detail of the matter to me.

December 1946 Signature: Nuri Sa’id

Author’s note: Nuri Sa’id negotiated with the Turkish president on Turkey’s territorial claims in Syria, without being authorized to do so.

Document 5:

The Syrian Ambassador in London to the Syrian Foreign Minister

Top secret

The Syrian Foreign Minister – Damascus

Mr Bevin summoned me and asked me to inform you of the following:

“Under the personal pressure of President Truman I ask the Syrian Government to give its agreement to the pipeline route, and the passage of Saudi oil and also ask it to give its agreement to allowing the outlet to be in Lebanon and not in Syria.”

This was his statement…. Then he set out for me the British point of view on the matter in a few words, “So Lebanon will finally be rid of France”.

Of course, he did not explain the meaning of his words to me. But the information I have been able to obtain here is that Great Britain was decided on placing the oil outlet in Syria and not in Lebanon, because it was counting on our friendship and because it was placing its hopes on the plan for Greater Syria which would make Syria into an instrument to its liking and because, in addition, it believed that Lebanon was a region where French influence could find a foothold.

The result that it now has before it is that America has definitively put its hand on Lebanon while it abandons us to the mercy of British policy. I believe that for us it is the most dangerous stage to pass through, for King Abdullah’s plan now becomes possible if America favors him to satisfy the demands of the Jews and of Great Britain.

My opinion is that we should look to Russia, as the situation is extremely difficult.

May 6, 1947

The Minister Plenipotentiary

Najib al-Armanazi

Author’s note: The Anglo-American conflict over the Saudi oil pipeline to the Mediterranean continued until Husni Za’im reached an agreement with the American oil company Aramco.

Discover more from Syria Comment

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Comments (3)

Eugene said:

So if I understand this, Israel couldn’t invade Syria, instead fought for it, just as it has done in the present? Back in the beginning, it was the British who were the bad guys, now it’s the Iranians. Yet, the Israelis need backing – military – because it doesn’t have enough to win over Iran, short of Nuclear bombs. Either Israel is a tool or it uses others. Which is it?

June 21st, 2018, 2:19 pm

Alif said:

If Israel truly desires peace it needs to stop its near genocidal policies against the Palestinian people. Slaughtering peaceful, unarmed protesters and turning Gaza into a prison camp are not the acts of a state that desires peaceful coexistence with its neighbors in the region.

June 25th, 2018, 6:04 pm

bruno said:

Samaria?….. Ok,we know where the esteemed professor is coming from.

So Israel has attacked Syria some 200 times and supports some of the Anti Assad forces,but claims not to be part of that civil war. Bizarre!

October 13th, 2018, 11:57 am

Post a comment